I have long said my dream job is to be a naturalist. Yet for many years, my outdoor recreation style was speedster. I was always looking to travel quickly and get a good workout. Then, in my late 20’s, I started hunting. I learned I had to move or sit quietly to have any hope of seeing animals before I spooked them. I began to appreciate slowing down and paying attention.

Outdoor Education

I have always loved outdoor exploration. As I paid more attention, my fascination with the complexities, interactions, and beauty of the natural world increased. Still, being a naturalist seemed about as likely as riding the range—a romantic, historical enterprise. Fast forward about a decade, and I stumbled across the Montana Natural History Center website. I found they offer and administer a course and certification called Master Naturalist. The focus of the program is to increase knowledge of Montana natural history and develop a corps of citizens dedicated to conservation education and service. It seemed too good to be true.

I researched further and found additional course options throughout the state, including Bozeman, Helena, Billings, Glacier National Park, and Swan Valley. Some condensed the 40-ish hours of instruction into one week, while others had weekly meetings over the course of several months. At the time, there were no options nearby, so I took a week of vacation time and attended the course in Missoula.

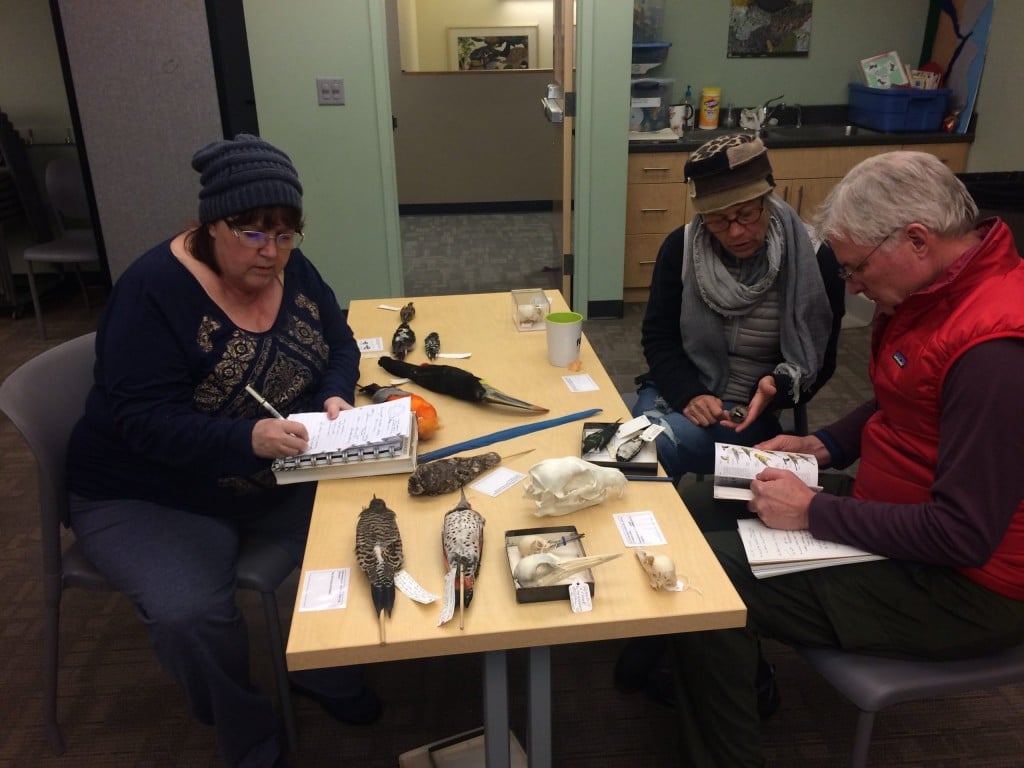

I loved it! We spent some time in the classroom investigating skull characteristics and insect orders. The bulk of our time was in the field though, watching, identifying, exploring, and sketching in our notebooks. The level of instruction was geared toward the layperson, matching my favorite definition of natural history:

“The study of the whole natural world, especially as concerned with observation rather than experiment, and presented in popular rather than academic form.”

Master Naturalist

Now that I’m a Master Naturalist (how cool does that sound?), I enjoy the outdoors even more. I like the opportunity to share knowledge with others and contribute to citizen science. To maintain certification, I annually complete 20 hours of volunteer service, plus attend 8 hours of continuing education. I refer to the Montana Natural History Center’s website for clarifying information and resources.

With COVID-19 we all have been forced to slow down. In some ways that’s a good thing. It’s worth taking the time to appreciate our surroundings. We can develop a sense of connection that extends beyond the human world…and develop relationships with our fellow Montanans too.

By Megan Martinez