Chronic wasting disease, or CWD, is that weird animal ailment you have almost certainly heard of even if you aren’t entirely sure what it is. For the uninitiated, CWD is a fatal neurodegenerative disease that affects all cervids (deer, elk, moose). The disease is caused by a prion (pronounced “pre-on” NOT “pry-on”) which is essentially, an infectious misfolded protein. Prions are not cells, they do not have a genome, they cannot reproduce in the way a virus or bacterium can, they are not alive. Instead, a prion seems to cause other proteins that it comes into contact with to also become misshapen, these defective proteins then accumulate in the nervous tissue, eventually destroying healthy tissue and killing the infected animal. Chronic wasting disease is in the same family as mad cow (bovine), scrapie (sheep), and Creutzfeldt-Jakob (human) disease. The CWD prion is transmitted cervid-to-cervid via direct contact with body fluids like saliva, blood, or urine, as well as contaminated soil, water, or food; in a sense, through anything, a cervid may come into contact with. And the fact that a prion is not a living organism with biological processes means they cannot be treated or prevented with antibiotics or vaccines. Additionally, the prion’s ability to remain in the environment for years makes it an incredibly difficult disease to combat.

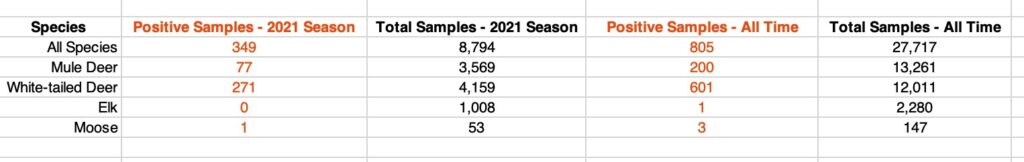

To date, infected animals have been found in 30 U.S. states and four Canadian provinces. Within Montana, we have found 805 CWD-positive samples out of 27,717 animals that have been tested since sampling began in 2017. Most of the research focuses on deer; this prion is typically known to infect more does than bucks yet infected bucks are more likely die1, 2. There is mixed data on whitetail versus mule deer susceptibility though the most recent data in Montana show similar rates of infection for whitetail and mule deer where their populations overlap3. That said, 5% of the whitetail deer sampled in Montana have tested positive for CWD, that is right at the threshold at which control of spread becomes difficult and more significant control methods may be needed4.

As far as we know CWD doesn’t infect anything except cervids. Even when cattle have been penned with infected deer for 10 years, they do not contract CWD5. And while there was one unpublished study that suggested macaques (a non-human primate) could get CWD from eating infected meat6 a second 13-year study found no evidence of CWD infection in exposed animals making it difficult to draw any conclusion about a species barrier and whether humans could contract this disease by eating an infected animal7.

So why is any of this important if the prion is generally located in nervous tissues which most of us don’t eat and there isn’t any evidence that we can get sick from it?

One reason this is important is that we don’t know what we don’t know. There have been relatively few studies about CWD transmissibility to humans or other species. This is due in part to the long incubation period of CWD, symptoms may not appear for years in an infected animal. And since there is no treatment or cure for CWD and it is highly transmissible among cervids only a select number of labs have the facilities to work with it properly and safely, further limiting the number of studies that can be done. So, while the risk appears low from what we currently know, best practice would be to not consume meat from a CWD-positive animal.

A second reason is that if we don’t work to limit the spread of CWD we are going to wind up with a lot more sick animals on the landscape. This will impact peoples’ desire to eat their harvested animals and it will change the age structure of the animals that are hunted. Because CWD takes several years for symptoms set in, an infected doe can reproduce for several years before she dies of the disease. However, the chances of those fawns being infected will be high as they will be in very close contact with their mother. The more fawns that are infected will mean more deer dying at a younger age from CWD which will ultimately lead to a loss of that older age class buck and the bigger antler set that comes with them. For most Montanans, pulling a moose tag is already a once-in-a-lifetime event and to see positivity rates of 2% already is alarming, especially for an animal facing many other disease and parasite challenges nationwide. And as Montana has been seeing a lot of recent controversy around elk management, a point not often mentioned is that if we continue to see large herds congregating on private land creating an easy avenue for group transmission, we will likely see a rise in CWD cases among those animals as well.

Given the transmission dynamics of CWD, its persistence in the environment, ease of transmission and difficulty to destroy, it is likely a disease that is going to be with us forever. So, what can we do to help? A relatively easy action is to call your representatives and urge them to support the CWD Research bill that is being presented at the federal level. This bill would provide the dedicated source of research and mitigation funds to understand how the CWD prion works and what we can do to control its spread. This disease is a nationwide issue and needs a nationwide program to address it. This prion has a lot of avenues to get around this country, infected animals migrate, predators that eat these cervids move, and hunters that travel to hunt are another potential avenue to transport CWD to new regions. This bill will hopefully fund more robust research into how this prion causes disease, how it’s transmitted, expanding testing capacity, and what best management practices are.

In the meantime, Montana could expand access to CWD check stations. The resources of FWP are spread thin but a program that “deputizes” regional businesses to collect samples could be a great way to get us to the level of access we would need for mandatory testing of all harvested cervids. For instance, FWP could provide a financial incentive for strategically located gas stations, sporting goods shops, and the like to have employees trained to retrieve lymph nodes and mail them to the appropriate facility. Alternatively, for better data acquisition FWP could send collection kits to anyone with an elk, deer, or moose license. A simple kit could include an easy visual guide to collect the harvest, plastic bags, and a paid-postage envelope. Making testing easy and free will ensure that we get the most data from hunters who are acting as citizen scientists by collecting these specimens.

The simplest act is to be responsible when you’re handling cervids, hunter or otherwise; dispose of carcasses in a dumpster that is taken to a landfill, especially if you are moving your animal out of the region it was harvested from. Montana FWP no longer requires you to leave the remains where you harvested an animal if you’re in a CWD priority zone, but they do require it to be disposed of in a landfill. When you dump your carcass remains outside, at trailheads, in ditches, you’re not only contributing to the poor image of hunters to nonhunters but also potentially contaminating a new site with CWD and aiding the spread of this disease.

CWD is a big issue and there is so much more to discuss than can be squeezed into an article here. If we are to effectively manage this disease and its impacts on cervid populations and the downstream ecological effects, it will take a nationwide concerted effort to effectively manage. Be responsible with your animal carcasses, talk to your fellow hunters, and let your representatives know that we need the CWD Research bill.

If you really want to dig in further on the issue of CWD there is a great 5-part series called the CWD Chronicles on the NWF Podcast in collaboration with Artemis Sportswomen.

- Edmunds, D. R., et al. Chronic Wasting Disease Drives Population Decline of White-Tailed Deer. PLoS One. 11(8): e0161127. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161127.

- Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) Surveillance Update: October 1, 2021. https://www.alberta.ca/chronic-wasting-disease-updates.aspx Accessed: 18 May 2022.

- CWD Annual Report from 2020. https://fwp.mt.gov/conservation/chronic-wasting-disease/management. Accessed 18 May 2022.

- Colorado Chronic Wasting Disease Response Plan. https://cpw.state.co.us/learn/Pages/About-CWD-in-Colorado.aspx. Accessed 18 May 2022.

- Williams, E. S., et al. Inoculation Challenge or Ten Years’ Natural Exposure in Contaminated Environments. of Wildlife Diseases. 54(3): 460-470. (2018). https://doi.org/10.7589/2017-12-299.

- Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD). https://www.cdc.gov/prions/cwd/transmission.html Accessed: 18 May 2022.

- Race, B., et al. Lack of Transmission of Chronic Wasting Disease to Cynomolgus Macaques. of Virol. (2018). doi: 10.1128/JVI.00550-18.

By MWF Ambassador DeAnna Bublitz

Bureau of Land Management staff securing willows in trucks and a trailer. Credit: Morgan Marks

Bureau of Land Management staff securing willows in trucks and a trailer. Credit: Morgan Marks