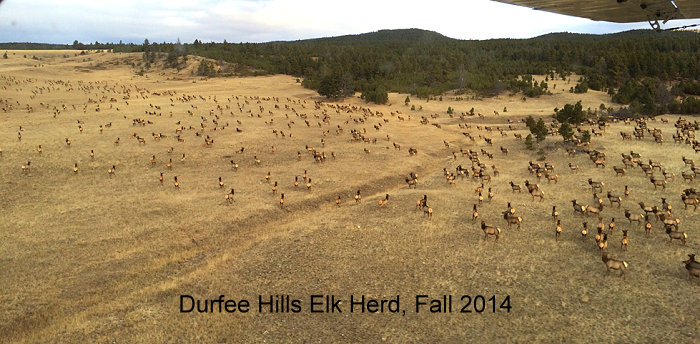

The Helena National Forest is rolling out a new amended standard that does not require any security cover during the hunting season. Flying under the radar has been a proposal to the change the security standard that has been in place for three decades.

Trees, officially, will no longer be necessary for big game security during the hunting season, according to the Helena National Forest. What has been a proven, science-based Forest Plan standard for wildlife security during the hunting season for 30 years, has involved a direct relationship between security cover and road density: the more roads within a square mile of public land, the more security cover for wildlife is required, and conversely less security cover is needed when fewer roads are present. But, at no time on public land has security cover been considered unnecessary — until now.

The existing old standard is based on decades of peer-reviewed research by dozens of wildlife researchers. There are no new studies that refute the long-standing science of wildlife security needs on public lands. That research focused on the need to reduce roads, but never did the science suggest that vegetative cover should be reduced as a component of security during the hunting season.

However, the decision has been made to amend the security standard to no longer require vegetative cover anywhere on the Divide or Blackfoot landscape that protects elk, deer, and other big game during the hunting season.

This insidious change is about to accelerate across national forest wildlife habitat, affecting fair chase hunting, and facilitating timber removal.

Montana wildlife can live in a dense forest without roads, but they cannot readily survive on treeless public lands with roads. And as wildlife find themselves less secure, they move to private lands where herds can no longer be managed through public hunting, where private landowners suffer game damage impacts, where commercialization of the public’s wildlife through outfitting too often becomes the landowner’s solution, and a frustrated public finds their favorite hunting spot in a new clearcut, devoid of big game.

On a variety of levels, the pending amendment to the big game security standard will have important consequences. Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks has agreed to the change in big game security if travel plans for the Divide and Blackfoot landscapes are implemented. But the consequences of treeless public lands will last for years and be manifest in game damage complaints. “Shoulder” seasons are now being implemented by FWP at the request of outfitters and some landowners to harvest wildlife displaced from what had been secure public lands. These “Shoulder Seasons” will occur on private lands – many of which have not been fully open to public hunting during the regular season, but before and after the regular season, elk will be pursued for up to 6 months – from August into February.

Denuding public land security pushes commercialization of wildlife into the hands of those who would “Ranch for Wildlife.” If they haven’t already, Montanans will soon realize that what happens to public lands will determine where public wildlife will end up, and whether they are privatized.

The decision to amend the Helena-Lewis & Clark National Forest security standard is pending. But there is still time to have a long-term positive effect for big game security by urging FWP to help keep public wildlife on public land, and by advocating for big game security in Forest Plan revision on the Helena-Lewis & Clark National Forest. Please, step up.

Gayle Joslin is a retired FWP wildlife biologist of 30 years, and member of Helena Hunters and Anglers Association.