The Bureau of Land Management’s new policy to conserve and restore wildlife movement and migration pathways by working collaboratively with state fish and wildlife agencies, Tribal nations, and private landowners will benefit fish and wildlife and is a positive step forward in tackling the nation’s biodiversity crisis. The new Instructional Memorandum provides valuable guidance that directs the agency’s state offices to consider fish and wildlife movements and connectivity pathways in land use planning.

“Wildlife must migrate and move in order to survive, so this new guidance to conserve and restore wildlife pathways will benefit elk, mule deer, pronghorn, and many species of fish,” said David Willms, senior director for Western wildlife and conservation at the National Wildlife Federation. “It is especially heartening to see the emphasis on collaboration with state and Tribal leaders and private landowners to connect and restore wildlife habitat and remove invasive species, which will have tremendous benefits for wildlife and humans alike.”

Restoration of wildlife movement to maintain healthy animal populations and promote human safety include wildlife-friendly fencing and wildlife crossings, which have both yielded successful results for minimizing wildlife-vehicle collisions as well as restoring wildlife migration pathways connecting across landscapes, especially for pronghorn.

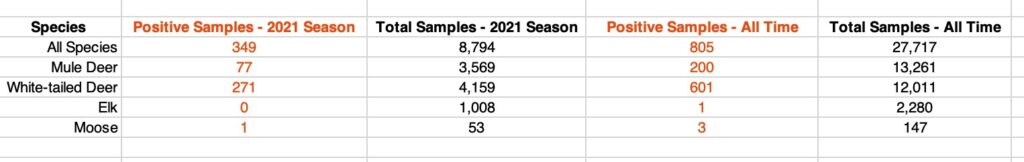

“More data is needed to identify such movements and wildlife migration routes,” said Naomi Alhadeff, Montana Education Manager at the National Wildlife Federation. “We’ve been working to gather Montanans together to use the app WildlifeXing, as a way to leverage community and citizen science to support gathering data. The data is used to identify hot spots and pinch points along Highway 2 and throughout Montana, where wildlife are seen on roadways, dead or alive.”

Wildlife crossings benefit more than just big game species; turtles, rabbits, coyotes, skunks, and myriad other smaller species of wildlife also utilize these crossings. The movement and migration of wildlife in the United States are vital to maintaining healthy animal populations. The continuing fragmentation and disconnection of habitat is resulting in increasingly isolated animal populations; the inability to reach important winter, summer, or breeding habitat; and higher rates of negative wildlife-human interactions.

“It will take intentional collaboration between federal, state, and Tribal land managers – as well as private landowners – to fully safeguard wildlife movement. We welcome today’s new guidance from the Bureau of Land Management. Now we need help from the public. We’re asking every person to download and input data regarding what they see along Montana roadways,” said Morgan Marks, North-Central Field Representative at the Montana Wildlife Federation. This data will be modeled at the end of 2023 so it’s crucial that as many people as possible serve as citizen scientists before that deadline.”

The National Wildlife Federation and Montana Wildlife Federation applaud the Bureau of Land Management’s new policy and commitment to work with state fish and wildlife agencies and Tribal nations to ensure that connectivity is an integral part of their wildlife management.

By MWF North-Central/Eastern Montana Field Coordinator Morgan Marks.

Feature photo by Director of Wildlife Programs at National Wildlife Federation Kit Fischer.